Blog

Since All Roads Lead to Home

Anjali Bhatia

As we are made aware, the elementary structure of transmission of the Covid-19 infection is made up of three constituents: infected person(s), uninfected persons(s), and the virus (exposure time), transmitted from the infected to the uninfected. The pandemic form is a serial replication of this structure of random transmission on a global scale, breeding in its wake, a culture of safety.

On this view, social and spatial dimensions cue the preventive measures of Covid-19 towards ‘social distancing’ or inserting ‘screens’ between persons through lockdowns, curfews, and masks. The measures aim to drive and incarcerate people ‘inside’ their homes so as to minimize random physical proximity between them, ‘outside’ of their homes. An emergent field of Covid-19 can be mapped along with the following stations: home (inside), the world (outside), hospital (quarantine), and final resting place. The home signals safety; the world, restrictions; quarantine, a waiting; hospital, the disease or its cure; and the final resting place, a fatality. There is a reconfiguration of existing spaces, carving out of new ones, and perhaps, the evaporation of old ones.

Within a span of less than a year, the ‘home’ comes out as a top contender for the person of the year epithet. Consequent to all roads leading to it, the home has become a hub of protection and refuge; a center of gravity; a black hole; and a fountainhead in the direction of which all out-migration must inflow. This epidemiologically safe notion of home is a window to the world; and the goings-on between it and the world is subject to state legislation.

The constitution of an epidemiological home at the hands of the Covid-19 is predicated upon the melting down of partitions, thereby bringing about a slippage between household, family, and home, each of which has distinguished analytical identities and careers in social science discourse. A household is associated with a residential and commensal unit, family with relations, roles, and functions, and home “as conceptualized in anthropologist Mary Douglas’s elegant essay, The Idea of a Home: A Kind of Space”, with space, regular cycles in structured time, and a moral community.

By far, since all non-familial domestic units and institutional residential establishments had to be shut down in adherence to social distancing, the general type constituted under the pandemic is a nuclear or extended family household. Subsequently, this familial household has come to fill the space of the epidemiological home. Melding structured space-time, normative roles, and relationships, and the dynamics of common residence, this epidemiological home is a hybrid entity under the combined jurisdictions of home, family, and household.

Now is an opportune moment to reflect on our respective taken for granted notions of home; its representations in popular culture as ‘home sweet home’, ‘shubh labh’ or, ‘sukoon’, or, ‘shanti kunj’ as these stand interrogated in plain view through contending meanings flitting through everyday conversations, shared experience, and social media constructions. A quick scrolling down the catalogue of these meanings brings into view diverse, sometimes counter-intuitive and deeply disconcerting associations of home such as, family time, healthy food, domestic chores, comfort, haven of safety, isolation ward, prison, retreat, leisure, pleasure, routine, chamber of violence, asylum, school, college, quarantine or workplace.

Arguably, out of all these meanings doing the rounds along with the virus, the subsuming of the workplace under the home, flags a fundamental and cataclysmic reconfiguration triggered by the railing of work into the epidemiological home. A detailing of the historic processes and conditions that had moved the workplace out of home would be simply too formidable for the delicate frame of this write-up to hold. In broad brush, these processes, integral to the transformations in the modes of production, division of labour, and the separation of the private and public spheres, had served as launching pads of modern societies. In a reversal, we are witnessing a home-coming of certain types of work, in particular, types that stand de-territorialized and repositioned to the virtual grid of the internet; and work-types that survived a well-wrought annihilation or suspension in pandemic conditions. Aamalgamating paid non-domestic work with domestic work (unpaid for members of the household) in the familial household and the epidemiological home’s doubling up as a workplace cannot but have unprecedented implications.

The articulation of work with the functions and norms of each of the three domains converged into the epidemiological home thereby leading to a face-off between the familial and professional domains. Assuming a lack of harmony between the two domains – owing to the mutually exclusive nature of non-domestic and domestic work and the demands on workers’ labour-time commensurate with wages received – clashes between the two seem inevitable. Exiting from work is hardly an option in these times when the certitudes of plenitudes or subsistence are a thing of the past. The financial health report of a world infested with Covid-19 will just about allow for fantasies of abandoning paid work even if the collision of work and family protocols are tearing apart the fabric of the day-to-day. This goes for most of the world’s wage earners.

In the event of this, what sort of considerations will determine our orientations? How will the clashes between protocols manifest in social relationships? Are old flashpoints going to get exacerbated? Will there be new flashpoints?

Given that the relations between persons inhabiting a home are familial, they are already under the jurisdiction of the institutions of family and marriage. With work moving inside and establishing another dominion, how will these relations be impacted? How will the existing relations, nested in normative expectations, respond to these developments? A better part of the answer to these questions depends upon the way in which the institution of the family responds to the imperatives of the work responsibilities of each of its members.

Since the allusion here is to paid work, it goes without saying that this leaves out of reckoning children, persons who are yet to enter the world of paid work, and the elderly who have exited it. This leaves us with working adults comprising men and women. In the context of home, these men and women are into familial roles and responsibilities, relationships and functions; age and sex-based pecking orders; gendered dynamics of decision-making, division of labour and violence; differential degrees of access to material resources and lines of authority.

Another ‘new normal’ is ‘loss of employment’. To be counted among the privileged for not having suffered this blow yet because of the portability of work, the twin identities – professional and familial – and the respective responsibilities of both, men and women have to be equally valued. This requires a gender equitable division of labour in unpaid and paid work, and in care work beside equitable access to technological wherewithal for facilitating professional responsibilities. All of this in the ‘odd hours’ of ‘liquefied’ and unstructured time.

In view of prognostications of a long drawn Covid-19 risk, it is urgent to put a finger on the epidemiological home for an early sighting of a prototype of a culture underway that might crystallize in course of daily routines as a ‘new normal’. It certainly germinates conditions that could open up possibilities of reconfiguring gender relations and fostering greater mutuality and co-operation.

Anjali Bhatia is an Associate Professor in the Department of Sociology, Lady Shri Ram College for Women, New Delhi. Her doctoral degree from the Jawaharlal Nehru University, (New Delhi) examined how the fast food eating out culture purveyed by multinational restaurant chain McDonald’s and its selective adoption by indigenous eateries, reconfigure family relationships creating tensions in global-local contexts. Her research interests are Sociology of Food, Family, Childhood, Youth and Middle Class. As a Guest Scholar at the Graduate School of Letters, University of Kyoto, Japan (June-July 2009) she delivered Lectures on the themes of Childhood, Courtship, Conjugality and Family in Globalizing India. She was an invited speaker at the Sagan National Colloquium (2012), Ohio-Wesleyan University.

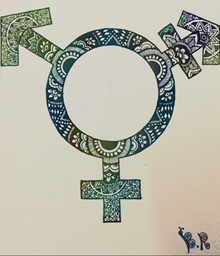

Ignorance is ‘NOT’ Bliss! Status of Transgenders in Higher Education

Bhumika Rajdev

CBSE declared the results of class 12th on 13th July 2020. These results play a significant role in the admission procedure for students in colleges as they determine their eligibility to pursue undergraduate courses. As per CBSE class 12th analysis, almost 10 lakh students passed class 12th exams this year out of which only 19 were transgenders.

It has been observed that central and state governments are delighted with the results of students as there is a rise of 5.38% in the pass percentage of class 12th as compared to the last year. Amidst this celebration, the participation of transgenders in school education and the steep fall in their pass percentage is worrisome.

There is a fall of 16.66% in the pass percentage of transgender students of class 12thin comparison to the results of 2019. Looking at the present number of passed trans students, only 15 transgender students would be eligible for undergraduate or higher education this year as opposed to lakhs of other students who do not fall under the trans category. This raises a serious question on the representation and accessibility of education for transgenders in our system.

To understand the status of their education, it becomes more than necessary to look at the current status of transgenders in India. According to the Census 2011 data, there are approximately 4.9 lakh transgenders in India and their literacy rate is 57.06%. Most of them belong to low economic backgrounds and have poor living conditions. Very few transgenders are able to pursue higher education. The reasons behind this can be seen in the challenges faced by them in schools’ premises.

Many transgender students drop-out from schools due to bullying and harassment. They are constantly labelled and stigmatised by their classmates and teachers. The school uniform, washrooms, and seating arrangements do not make them feel included part of the system and constantly excludes them from the ‘mainstream population.’ When they are unable to complete their schooling, then how can we expect enrolment and participation of transgenders in higher education?

Transgenders are one of the most neglected community in our education system. They have recently been acknowledged by the state and educational institutions as ‘Third Gender’, but their needs and requirements for dignified spaces in the system have been completely ignored. CBSE results analysis has also exhibited this biggest loophole of our education system with respect to gender equality.

Hence, it is high time for deliberation on the ideas of gender inclusivity and trans-friendly campuses. Sensitization programmes, workshops, and awareness campaigns on ‘sexual identity and Gender’ are the need of this hour. School and college campuses must be safe spaces for transgenders. It will not only help in their upliftment but will also make our system egalitarian and progressive in nature. This can only be done if the state and educational bodies take off their ‘veil of ignorance’ to accept the harsh reality of transgenders in our country and give due attention to their concerns.

“Where ignorance is our master, there is no possibility of real peace”. – The Dalai Lama

Bhumika Rajdev is a B.EL.ED graduate from LSR and has completed her Masters in Political Science. She has worked in various public and private schools. Currently, she is working as TGT Social Science in a school-based in Delhi. Bhumika loves to write and speak on contemporary issues in the area of education.

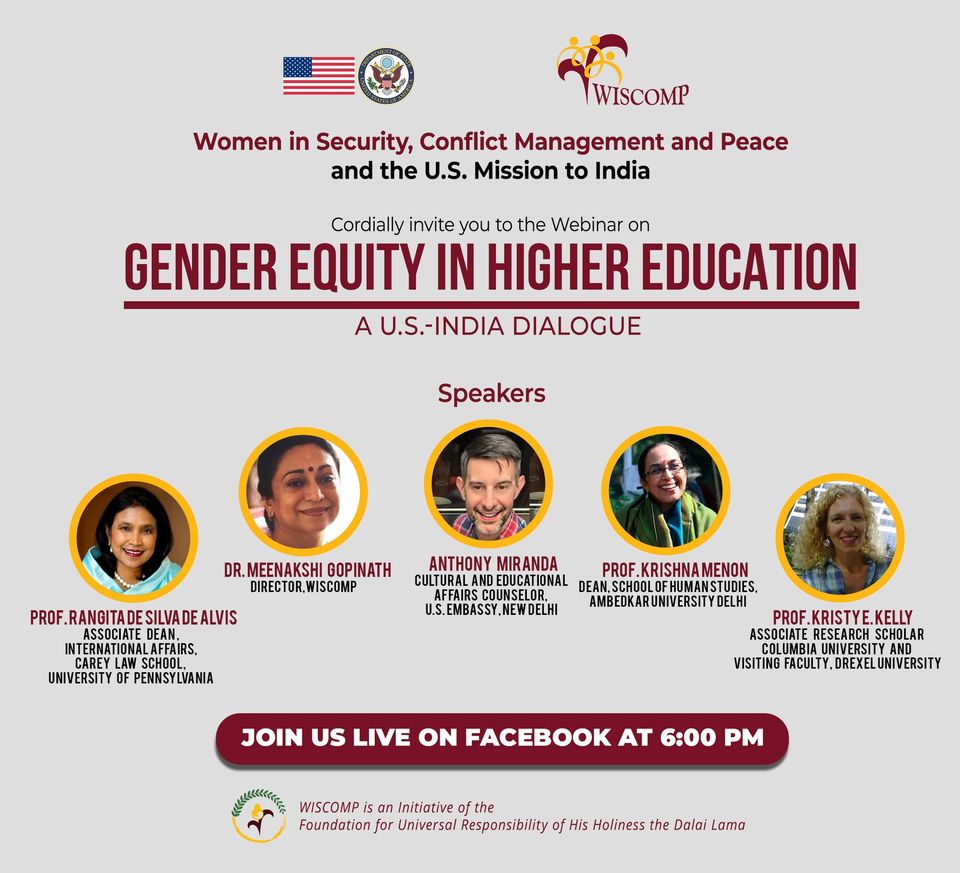

Gender Equity in Higher Education: A U.S.- India Dialogue.

Have you missed WISCOMP’s Dialogue between the policymakers, senior professors, and educationists in India and the U.S. on ‘Gender Equity in Higher Education’? You can watch it on our Facebook page.