Blog

Rada Akbar

For Rada Akbar, art is the medium through which she expresses her own thoughts and the grim reality surrounding her life living as a woman in Afghanistan. Starting her career in visual arts as a painter, she now uses photography to narrate stories and document the life of Afghan people, specifically women.

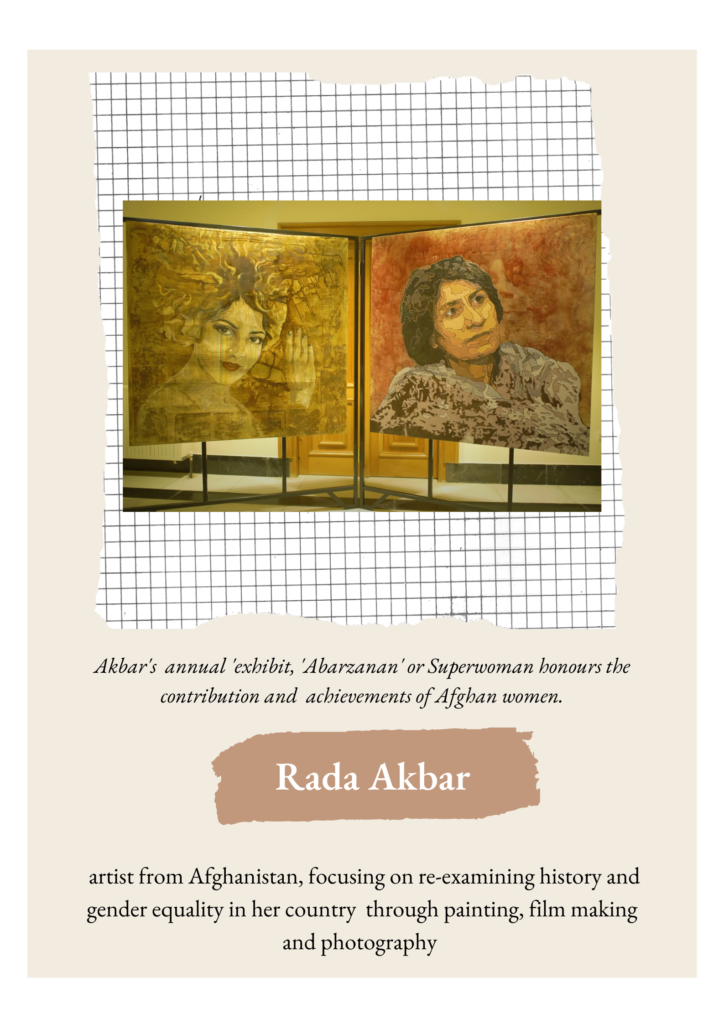

If for the Taliban their skewed interpretation of the sharia law is a tool for oppression, then for Akbar her camera lens is a tool for justice.Braving threats and beating all odds, Akbar has successfully put a number of exhibitions, both offline and online, which provide not only a scathing commentary on the status of Afghan women, but also honours them as survivors who refuse to bow down even in the face of difficulty . For instance, her project Abarzanan (Superwomen) is an ode to the courage and resilience of Afghan women who braved patriarchal oppression. This exhibition includes the installation of female mannequins, honouring Afghan women who’ve carved their own way to success in an intensely oppressive culture . These include poets, mountain climbers, politicians, TV presenters, musicians and others who rose to fame in Afghanistan. Not only does Akbar’s exhibition celebrates the achievements of women, but her work also pays homage to women who lost their lives because they lived in an oppressive society that curbed women’s freedom. One such woman is known as Rokhshana, a 19-year-old from the central Afghan province of Ghor, who was stoned to death for her refusal to agree to a forced marriage. In Akbar’s own words, her work reminder to all those powerful men that Afghan women refuse to submit to the boundaries created for them or suffer in silence.

Sources

Sahraa Karimi

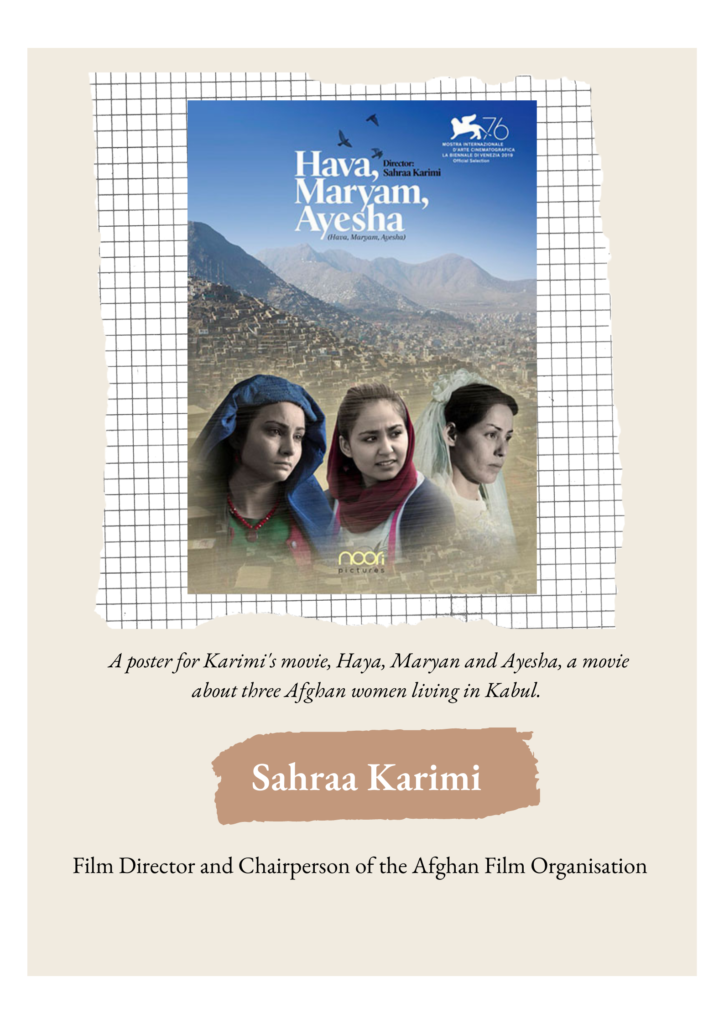

Film maker and activist, Sahraa Karimi was the first woman to head Afghan Film back in 2019. She is also a director, and her debut feature, Hava, Maryam, Ayesha, a women-centric project, was the first fully Afghan production in a long time. The movie was filmed entirely in Kabul in Afghanistan and the cast consisted of Afghan actors. It went on to receive critical acclaim at the Venice Film Festival. The movie is a poignant and humanistic portrait of the intricacies of gender, culture and class, and the ways in which Afghan women are fighting to take back the reins of their life in their very hands.

Karimi is of the opinion that the film fraternity and artists in general have a political and social responsibility towards the society. For her, film making is not some simple entertainment, but has the potential of acting as an agent of change, a view that puts her at odds with the previous Afghan governments that didn’t invest in arts and cinema. In a virtual conversation with Afghan-Canadian director Tarique Qayumi, she reiterated that “filmmakers should raise their voice and push decision-makers not to recognise the Taliban.” [I] Recognising the power that art and artists hold, she published an appeal right after the Taliban takeover of her country for filmmakers around the world to join in an act of resilience and tweet out the hashtag #DoNotRecogniseTaliban.

Her next project, tentatively titled Flight from Kabul is unlikely to be filmed in her home country, now under Taliban rule. Instead, her project will capture the state of transit through which every Afghan that fled the country in search of refuge had to go through. For Karimi, it is important to document the plight of Afghans as it the only way through which she and others like her can get over the trauma.

Sources

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sahraa_Karimi

- https://www.dw.com/en/sahraa-karimi-to-direct-a-film-on-her-flight-from-afghanistan/a-59110698

- https://www.fairplanet.org/story/sahraa-karimi-the-world-has-to-know-other-stories-from-afghanistan/

[I] As quoted in her interview with Tarique Qayumi as part of the five-year campaign called Share Her Journey.

Sara Barackzay

Sara Barackzay is 24-year-old animation artist and one of the very first and few in her country to follow animation arts professionaly. For Barackzay, who lost her hearing as a child, animation was a universal language which presented her with a world full of possibilities. Despite the lack of support from her extended family members, she left Afghanistan to study in Turkey on a fully funded scholarship. After completing her degree, she returned back to Afghanistan with the dream of introducing a specialist school for animation arts, a rarity in Afghanistan. Her dream was solidified when she finally founded the course called Nasl-e Musbat or Generation Positive and held around 30 digital arts courses in Afghanistan.

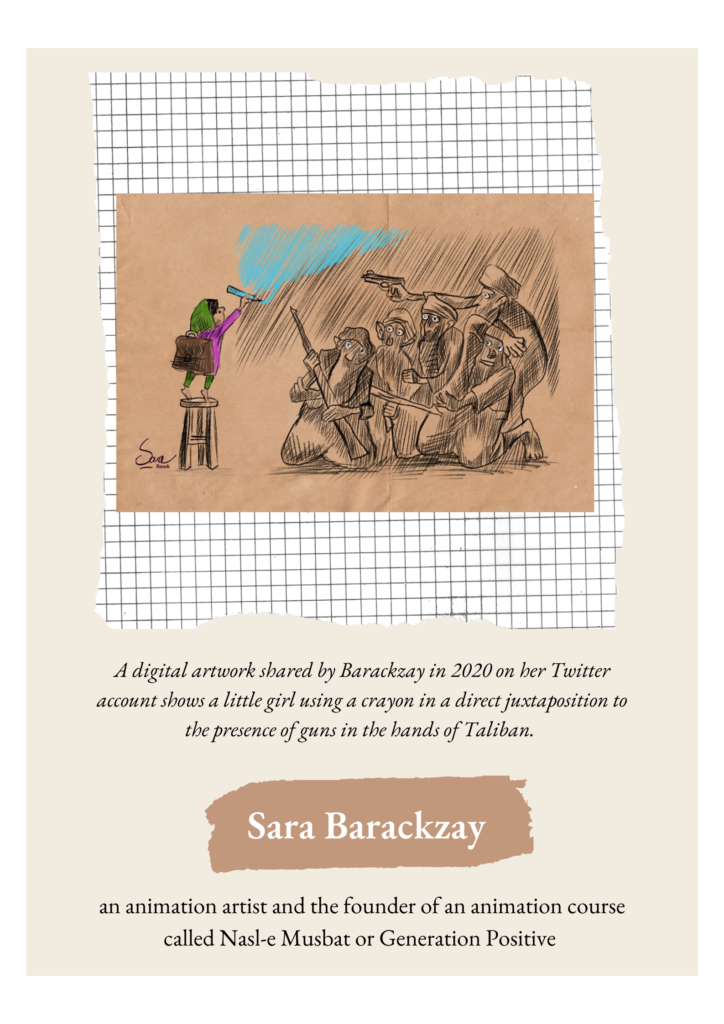

Barackzay ardently believes that animation is a medium through which Afghanistan’s problems and its very vibrant culture can be better explained and described. As opposed to the dominant discourse on Afghanistan as propagated by international media, her illustrations bring in a new perspective in our understanding of the region. She primarily uses animation to tackle the stereotypes and misconceptions about her homeland and show the world that Afghanistan is much more than the Taliban and decades of wars. Through her art, she attempts to pay homage to her culture and share her skills with other women who dream of becoming animation artists.

Her commitment to women’s rights is evident in her work: scenes of an Afghan woman breaking open prison bars or a young girl dancing without a concern in the world amidst scenes of war. Despite the threats, she teaches other young Afghan women her skills and hopes to make their future. However, Barackzay’s achievement are just not limited to her work on women’s rights and peace, she has successfully created drawings for children’s book projects with the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) and UNESCO. These drawings are meant to help children who are unable to go to school with learning.

Sources

Lida Abdul

Lida Abdul is the first artist from her country to represent Afghanistan at the 51st edition of the Venice Biennale in 2005. Her art explores issues of migration, remembrance and memory through performance and video. Born in Kabul but forced to leave her country with her family after Soviet invasion, Abdul’s work provides a thorough examination of the role of monuments and ruins in contemporary culture as a counter-narrative to dominant preoccupations in the politics and meaning of the built environment. It is her itinerant past and present that informs her perceptions of home and space.

Abdul considers herself as a nomadic artist whose art explore notions of homeland and exile, in which the battle-scarred landscape of Afghanistan is a central character. Using film, photography, installation and live performance, she is invested in exploring the aftermath of war from the perspective of Afghans who have no choice but to live with the seemingly never ending destruction and chaos. It is her focus on bodies and landscapes and their complex interaction that she is able to create compelling pieces that critique the legacies of war.

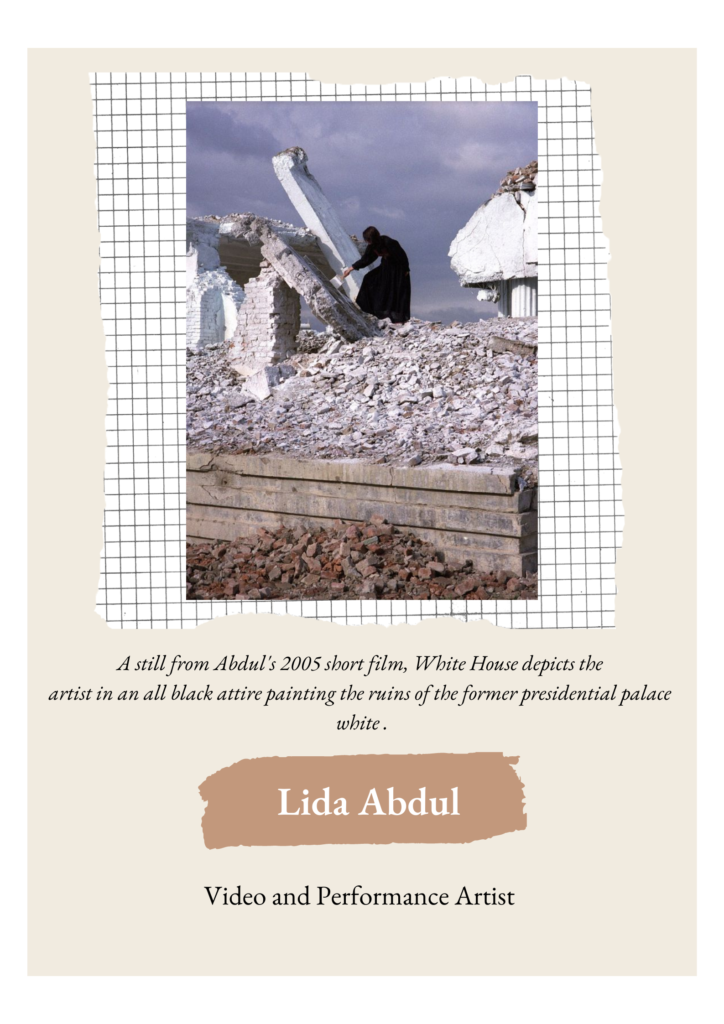

In one of her most well- known short films, White House (2005) she takes on the hypocrisy of the American government that under the garb of the redevelopment of Afghanistan is actually benefitting only American conglomerates. The five-minute- long film is shot in the outskirts of Kabul, where we see the black-clad artist painting white the bombed ruins of what once the former presidential palace. The act of painting the rubble with white paint is at once absurd and futile, but the gesture of whitewashing is loaded with symbolism in Abdul’s film. The bombed building in the film is a structure, a part of the built environment that predates the ‘War on Terror’ and is a witness to the violence that the war has unleashed. As opposed to monuments that “cover things up” and present a re-branded history, ruins “preserve the history” as Abdul explains[i]. They remain standing as reminder of loss and a promise of revitalization that is still to come. Through the film, Abdul avoids falling in the rhetoric of mourning and forgiveness by keeping intact what remains of the past—the ruins. She revitalises the ruins to open up new spaces of thinking about society, identity and history.

Sources

- https://www.guggenheim.org/artwork/artist/lida-abdul

- https://2017arth4919.files.wordpress.com/2017/01/cavallini-on-abdul.pdf

- https://www.artsy.net/article/artasiapacific-20-slash-20-lida-abduls-white-house

- https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/eascfa/about/feminist_art_base/lida-abdul

[i] See Lida Abdul’s interview in Roberto Cavallini paper titled “Counter-monuments and promise: reading Lida Abdul’s ‘White House’ and ‘Clapping with Stones’ video-performances”.