Johanna Rabindran

I’ve spent hundreds of hours poring over floor plans, the more complicated the better. I trace the path from bed to doorstep. I squeal over open corridors and tiled balconies and rooms built around a central courtyard. I’ve designed libraries, schools, palaces, tree-houses, bookshops, gardens and toy-rooms, all for the sheer pleasure of imagining what it’s like to live in a different space.

All of this is to say, I’m surprised that it took me so long to notice kitchen design. Like with all other spaces, the design and form of a kitchen are inter-connected with its use and function. There are many things which can be said about kitchen design (the separation of dish-washing and cooking sides, the counter-tops, storage space), but today I’m writing about open and closed kitchens.

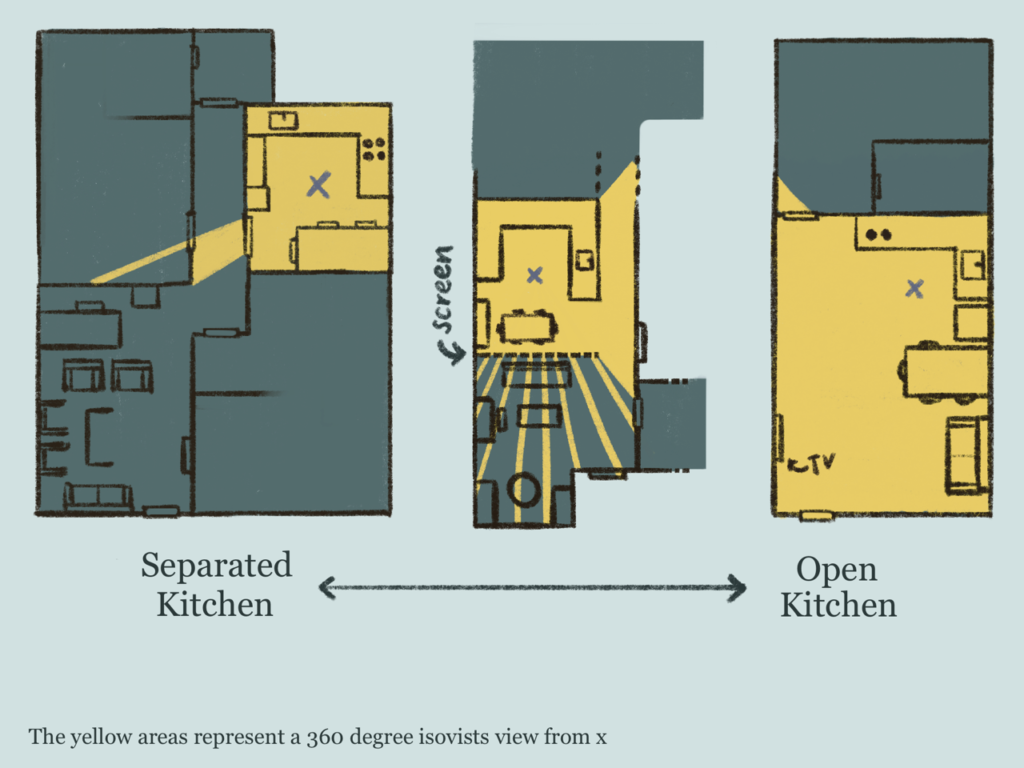

Usually located at the back of the house and separated from the rest of the living spaces, the closed kitchen is a world of its own. On the other hand, the open kitchen is more, well, open. In this design, the kitchen space is integrated with the dining room and living room. If you’re feeling particularly nerdy, you could make a scale, from the extremely isolated kitchen (left) to a fully open living space (right). In between are the kitchens with windows cut out and kitchens separated by a screen rather than a wall.

I think open kitchens are more democratic. In most families today, the women are still largely responsible for feeding the family and keeping the kitchen in order. Constructing the kitchen as a separate space (both literally and figuratively) is a kind of exclusion. In a typical closed kitchen, you keep walking away from the TV and you miss bits of the story. You miss the conversation happening around guests. More importantly, when the women and girls are preparing lunch in an open kitchen, the men cannot just sit and watch TV passively. They are compelled to notice the labour being done. Maybe they will even get up and help.

So why would someone set up a wooden screen to separate their open kitchen from the living room? My mother recalls a gathering at the house of some family friends who had just finished building a home with a shiny new open kitchen. We were all pitying her, she says. You enter the house and there’s the kitchen. That family later built the screen to create some semblance of privacy.

While shopping around for a new apartment, my mother was drawn to one with a large square kitchen, plenty of counter space, and a proper door (instead of just a doorway). Things tend to get messy. Imagine you’re cleaning chicken, she says, and a vegetarian neighbour drops in to say hi. With an open kitchen, the smoky smell of chapatis, the milk spilled on the counter-top, the piles of dirty dishes all hit you as soon as you walk in through the front door.

She says she can’t talk to guests and finish up meal prep at the same time, and if she really wants to watch a movie on TV, she’ll just record it, or cook later. Besides, she continues, I need my space in the kitchen. My mother is a food blogger and passionate cook, so she would know.

Personally, I despise missing bits of movies and conversations when I go help in the kitchen, so I’m inclined towards an open floor plan. I don’t intend to spend too much time cooking (I’ve already decided that I will cook in bulk on Sundays and Wednesdays). When I cook, I’d like to hang out with my house-mates or family. My mother likes to be alone in the kitchen. I think cooking is lonely work.

But then again, my sister and I like to kick our parents out of the kitchen, shut the door and go wild. We play a Hamilton playlist, invent our own recipes and sneak extra eggs into the noodles. I like these evenings, when we laugh and talk about secrets and favourite characters. In an open kitchen, our parents might overhear, and my mother might keep an eye on how much pasta sauce we use.

So where does this leave us? Maybe to claim that open kitchens are universally emancipatory is to overlook the lived experiences of those who use the kitchen. The only thing I can say for sure is that we need more considerate design. Privacy and openness are perhaps more fundamental problems than deciding where to put the dustbin or how many cabinets to build.

A student of Political Science, Johanna Rabindran has written previously for Katha, an NGO, as well as the history journal and political science newsletter of Lady Shri Ram College. She has also served as editor for Sabab, the department journal. Her research interests include language and politics, political theory, feminism in practice and media. On quiet days she drafts her first novel, makes digital art and raves about her favourite books (The Name of the Rose, A Man Called Ove, and A Passage to India!).